A behind the scenes photo of West Germany’s cross-country radio program RIAS, which was the most popular among East German citizens during the country’s separation in the Cold War. Image: RIAS |

The role of media such as television and

radio is known as a crucial element in German unification. Since East Germany

first permitted East-West TV broadcasts in 1970, Eastern citizens were able to

easily access unbiased information through West German programming. However,

even before that, East Germans were able to gain exposure to West German media

immediately following their separation using illegal means. West Germany sent

information to East Germans about the free world through shortwave radio,

loudspeakers, and leaflets, despite the fact that East Germany tried to block

these efforts using measures like radio signal jamming.

After the country’s division, East Germany

was ruled by an autocratic leadership and was cut off from the outside world.

Despite the East German government’s tactics of punishing listeners and signal

jamming, East German citizens braved the consequences because of their longing

for freedom and information. In this regard, they are similar to pirate radio

listeners in North Korea. Regional experts generally agree that media played a

significant role in changing the perspective of East Germans, inspiring them to

demand freedom of travel to the West, and setting up the foundations for their

protests and planning for unification.

The West German government’s publicly

produced radio played a big role in enlightening the East German people. Just

like today’s situation with North Korea, it was not possible to send a TV

signal to East Germany in the early days. In the 1950s and 1960s, radio

broadcasts were beamed across the border to inform the East German citizens of

the outside world. The Soviet Union was the first to launch a propaganda

broadcast station in the East European bloc. The American led allies

established the Rundfunk im amerikanischen Sektor (RIAS, or Broadcasting Service in the American Sector) radio station on the Western side. After the official

partition of Germany in the Cold War, other allied stations also sprang up,

such as Deutschlandfunk and Deutschewelle.

At the same time in East Germany, all

information being reported came out of the Socialist Unification Party. As part

of an effort to gain an advantage and block foreign influence, they retained a

monopoly on media dissemination. This ensured that no information from the

outside world contradicted the official state positions. On the other

hand, West Germans were privy to reports that updated them about the situation

in East Germany. They were also given access to satire and dramas that depicted

the lives of East Germans. For these reasons, the East Germans had more faith

in the West German media than in their native media outlets.

RIAS editor-in-chief and Deutschewelle

reporter Hans Jürgen Pickert said, “RIAS and the other broadcasters were

originally set up for a West German audience. But the production crew was dead

set on making the signal reach into the East. The East German citizens were

doubly enticed because they know that the same programs they were listening to

were trusted and enjoyed by the West Germans.

An anonymous representative from the Bundespresseamt (Federal Press Office) said, “The West German radio

stations were not devised to change East German thinking or destroy the

Socialist government. They merely focused on conveying information about the

West German people’s daily life. Unexpectedly, this sort of natural style of

broadcasting ended up enlightening a large amount of Eastern listeners and even

helped in eliciting political changes.”

From the 1960s West Germany transmitted

Public Television Station One (Das Erste) and Two (ZDF) into East Germany.

These channels includes news, entertainment, and cultural programming. In the

1970s, the broadcasting of West German stations into the East became even more

widespread. East German native and head of Stasi Records Agency (BStU) Roland Jahn said, “Up until the 1960s, watching TV

from the West was a punishable offense, but it couldn’t hold people back. We

lived in East Germany during the day but in West Germany at night. In the

1970s, there was almost a tacit tolerance for the viewing and listening of

outside media. The Eastern government simply couldn’t hold back the barrage of

interest in Western media.”

The Social Democratic Party’s Willy Brandt

launched the “Look East Policy.” It started to gain momentum at the start of

1973. Up until that point, cross-country communication was limited to

disseminating leaflets across the border and using loudspeakers at key

locations like the Berlin Wall. In the case of the leaflet dissemination, many

departments were involved and it was a thoroughly prepared strategy.

Robert Lebegern is director of the

Deutsch-Deutschen Museum Mödlareuth (Mödlareuth Border Museum). He said, “Western Europe used everything from

rockets, balloons and wind to spread the leaflets. They would release

approximately 500-1000 A4 sized papers at once into East German regions. On the

Eastern side, teachers ordered students to collect the leaflets and then the

Stasi would do an investigation.”

Director Lebegern also said, “For the most part, the loudspeaker broadcasts

went from East Germany to West Germany, but there were also instances of young

people from the West engaging in regular, organized broadcasts using

loudspeakers near the Berlin Wall. These youngsters built a temporary

studio and relayed the news through megaphones.”

“Without the cross-border broadcasts, there

would not have been any peace protests.” According to experts from East

Germany, the West German broadcasts provided “a window to the world,” “a means

to find the strength to go on living,” and “a door to a new consciousness.” But

these broadcasts did not simply convey information, they also provided an

indirect framework for the East Germans to understanding what it meant to live

in a free country. It also stimulated anti-government sentiment and laid the

foundation for unification.

East Berlin native Anna Kaminsky served as

executive director of the Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der

SED-Diktatur (Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of

the SED Dictatorship). She said,

“the East Germans who longed for legitimate news and information for so long

did not keep these sources to themselves when they found out how to access West

German radio and TV. They went around discussing the content with their

friends. After interacting with and sharing this content, East Germans began

reflecting upon their own lives. This led them to the difficult task of

recalibrating their mentalities. This type of consciousness grew into the

democratic protests and the border reforms.”

Director Kaminsky continued, “It

is certainly true that the oppressed Germans of the Soviet Bloc were in need of

unbiased information, but I think they needed something more than that. They

needed to hear that they were not being left behind by the free world. They

needed some sense of connection with the Western part of the country.

Cross-border broadcasts thus served both purposes: provided information and

assurance.”

Herbert Wagner was an enthusiastic listener

of Dresden’s Deutschlandfunk and Deutschewelle broadcasts and now serves as the director of Gedenkstätte Bautzner Straße Dresden (Former interrogation prison for District

Dresden of the Ministry of State Security of the GDR) He said, “Western broadcasts gave us

the energy and courage to carry on under difficult conditions and oppression.

If there were never any broadcasts, I likely would have thought that the West

had forgotten about us, and was content to enjoy their freedoms without trying

to assist us. I think the broadcasts became a sort of door for me to use

to escape my immediate surrounding and understand the world at large.”

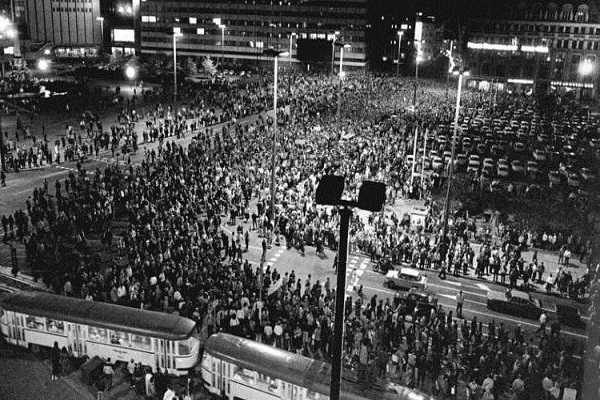

Jürgen Reiche, Secretary General of Zeitgeschichtliches Forum Leipzig (Leipzig’s Forum for Contemporary

History), remarked that, “even though the

revolutionaries in East Europe did not know one another in the beginning, the

radio broadcasts brought them the information they needed to understand the

true situation. This helped set off a powder keg of anti-government sentiment.

Just as 100,000 people gathered together to start a revolution for peace after

hearing the West German broadcasts in East Germany, South Korean radio

broadcasts into North Korea will have a large impact in terms of influencing

the mindset of North Koreans,” he concluded.

*This article has been brought to you thanks to support from the Korea Press

Foundation.