Former pro-North Korea student activist Kim Young Hwan. | Image: Daily NK |

Kim Young Hwan is the same human rights

activist that Chinese state security agents arrested and tortured over 114 days

between March and July 2012.

Despite his prolonged incarceration, the Chinese authorities never charged Kim with

a crime, and are therefore the only ones who know why he was arrested at

all. Kim believes they didn’t even know who he was in the beginning; in his

view, they just arrested him because he happened to be with activists who were under surveillance at the time. It was only later, once his

importance had been established, that Kim was accused of conspiring against the Chinese state. They would later threaten to pass him over to the North Koreans.

This was not a trivial threat. Kim’s Chinese interlocutors knew very well that

the North Korean security forces would be overjoyed to get their hands on Kim.

Why? Because in the 1990s, he directly and very publicly betrayed Kim Il

Sung.

It was back in 1991 that Kim made his secret trip to Pyongyang. At the time, he

was a youthful activist with an extreme, and extremely critical, view of the

South Korean government of President Chun Doo Hwan, a military dictator who had

taken power in a coup d’etat. A law student at Seoul National University, South

Korea’s premier academic institution, Kim’s anti-government activism in the dying days of the 1980s earned him a spell behind bars.

Following his release in December 1988

after two years and a month in prison, Kim joined an underground organization

founded by fellow law classmate Ha Young Ok. The “Anti-imperialist Youth Alliance”

was styled after a group established by Kim Il Sung in his own youthful

revolutionary phase. There, Kim Young Hwan organized the distribution of

pro-North Korea materials to colleges and factories as part of birthday

celebrations idolizing Kim Il Sung. He hung signs praising Kim and his son, Kim

Jong Il, and conducted study sessions eulogizing both the core tenets of Juche and

Kim Il Sung’s prowess as an independence fighter.

North Korean operatives soon took note of Kim’s

acumen in organizational matters, and concluded that they should recruit him to

the “revolutionary” cause. Thus, one day in early July 1989, he received a request

for a meeting from a man who identified himself as Kim Cheol Soo. The man would

later be revealed as Yoon Taek Rim, a known North Korean agent.

When the two men met, the middle-aged Yoon explained: “I have come from the North, Mr. Kim, and wish to discuss unification with you.” But Kim, understandably skeptical and fearful of South Korean intelligence agents, retorted: “How can I be certain that you are

from the North?”

“Ah yes, I see,” Yoon concurred. “Then I will take

steps to help you confirm it. Listen to the broadcast from Pyongyang at 22:00 tomorrow night. The announcer will state that ‘I have made contact with Mr. Kim

and delivered the message.’ This will prove my identity.”

Kim listened to the broadcast as instructed, and sure enough the North Korean

announcer did exactly as Yoon had said he would, convincing Kim that the story was true. Yet Kim felt ambivalent about meeting “the man from the

North” again. He was already a core member of an underground movement philosophically

based on the Juche idea, and he desperately wanted to see North Korean society

for himself and discuss Juche with North Korean experts. But now that this

appeared to be coming to pass, he found himself with much to ponder.

Despite these doubts, Kim went on to meet Yoon

six or seven times, all while doing things like hiking up and down Mt.

Gwanak, an urban mountain in the south of Seoul. Yoon brought Kim into the

Chosun Workers’ Party in a ceremony held on that very mountainside, getting him to

pledge undying loyalty to the Party and to Kim Il Sung. Prior to his

departure back to the North, Yoon also gave Kim a shortwave radio, codebooks

and a numbers chart for interpreting broadcasts from Pyongyang. Every two

months, a series of numbers was broadcast containing instructions for all

personnel in South Korea, including Kim, who by then was known by his handle: “Gwanaksan-1.”

In February 1991, the numbers called Gwanaksan-1 to Pyongyang. He was instructed to come

at an appropriate time, but moreover to “bring someone with you who can organize and

manage our communications effort.” Kim called on a former colleague who had just been released from prison. “I am going to take part in an

important and dangerous task for the sake of unification,” Kim told Jo Yu Sik. “Can

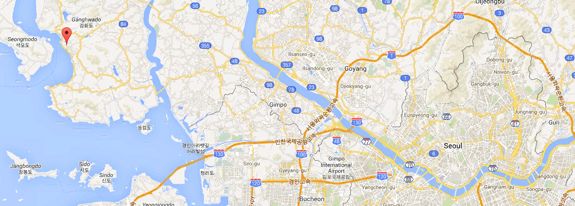

you do it with me?” Jo agreed, and at midnight on May 17th that year the two men rendezvoused with two North Korean agents on a beach at Geonpyeong-ni, on the west coast

of Ganghwa Island (see image).

Almost five hours later, the four men arrived by submarine in the

North Korean port city of Haeju, where two ranking Party officials were waiting.

To be continued…